The €3 Trillion Shrinking Pile

When trillions saved could actually be a bad thing

1. The Pile

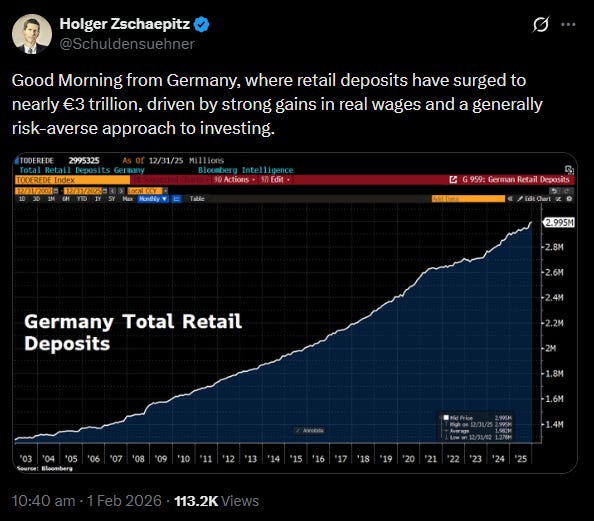

A few days ago I saw a tweet about German bank deposit balances — at first glance it seemed positive, but for some reason I couldn’t stop thinking about how enormous that number actually is.

Nearly €3 trillion. That’s what German households hold in bank deposits. Largest pile in Europe. It sounds solid, gives you an almost tangible image of a vault carved into rock somewhere.

But when you start asking questions, it deflates fast. Does it generate investment returns, is it roughly enough as a retirement supplement, that kind of thing.

Divide by 41 million households and you get about €72,000 per family. Not nothing, but not a war chest either. Germany’s public pension replaces roughly 44% of gross pre-retirement income, below the OECD average of 51%. The gap between that and a comfortable retirement is pretty vast. Even modest estimates — something like 30k a year over 10–15 years — point to around 450k needed per household. Oops.

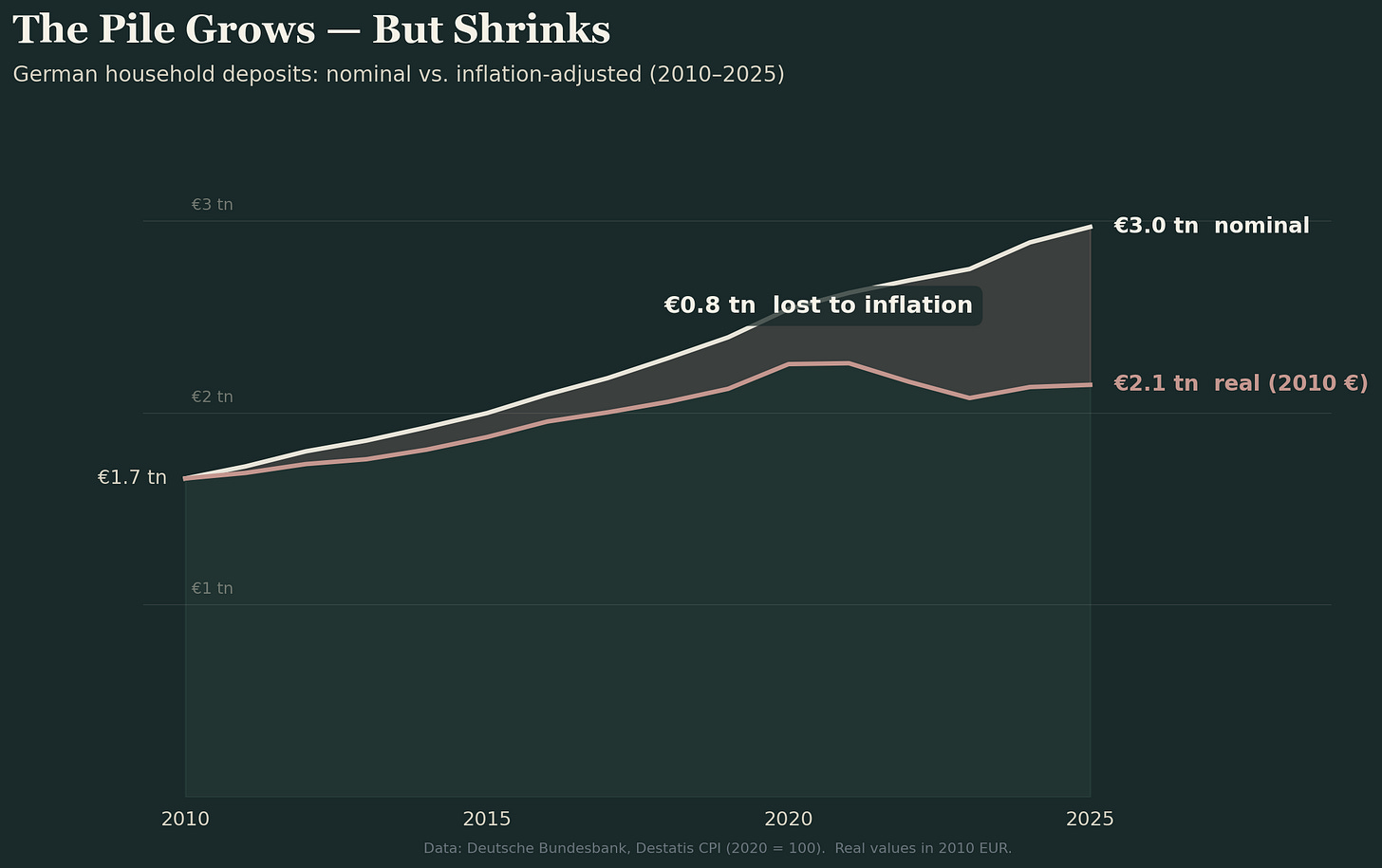

And worst of all, it’s not even growing in real terms. At the end of 2010, German households held €1.7 trillion in deposits. By end of 2025, nearly €3 trillion. That’s 79% nominal growth, which sounds healthy until you subtract 38% cumulative inflation.

The pile isn’t evidence of German financial strength. It’s inadequate savings earning almost nothing, slowly losing purchasing power in accounts designed for liquidity, not wealth building.

2. The Leak

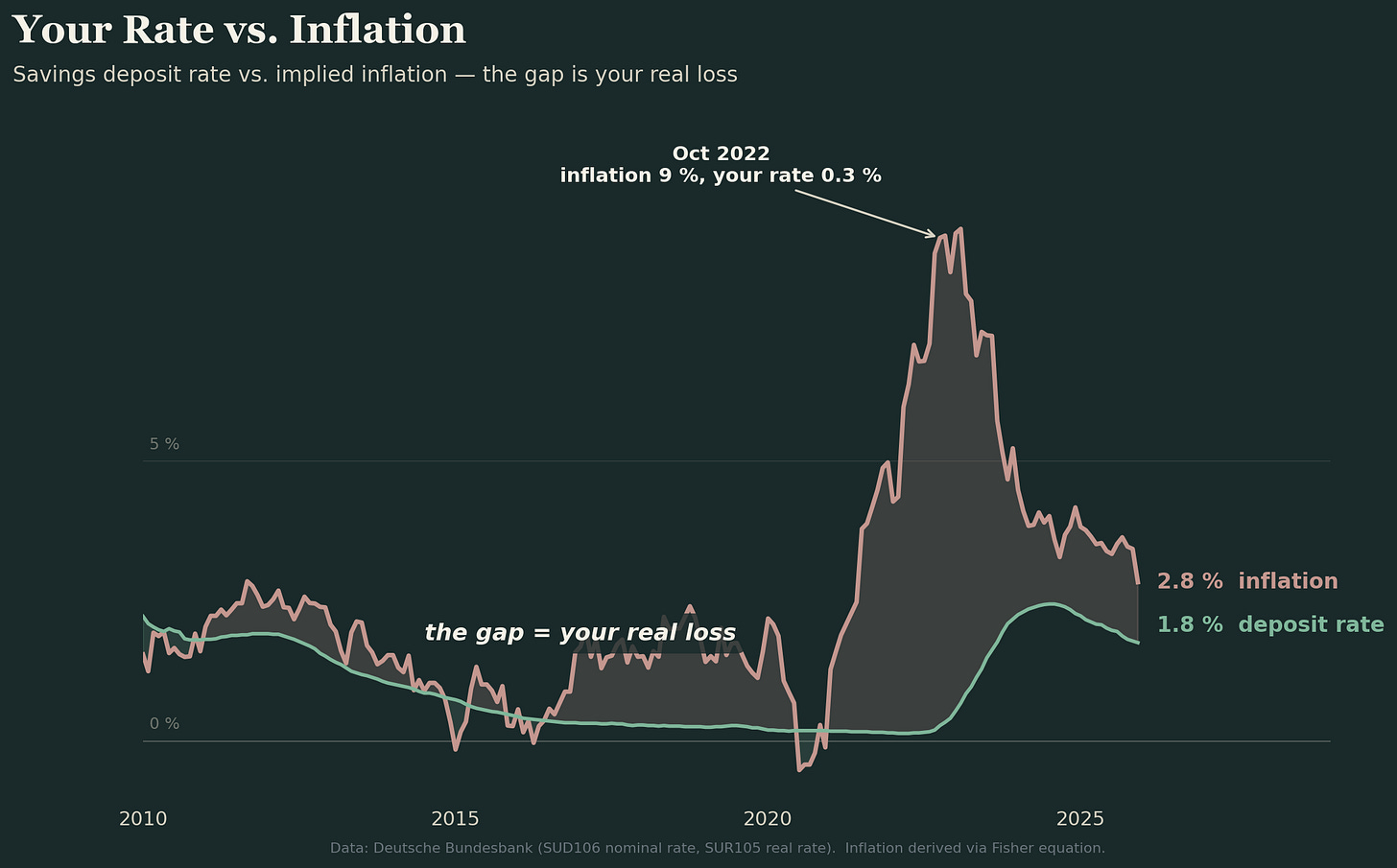

Here’s the thing that seemingly a lot of people never quite internalize: real interest rates.

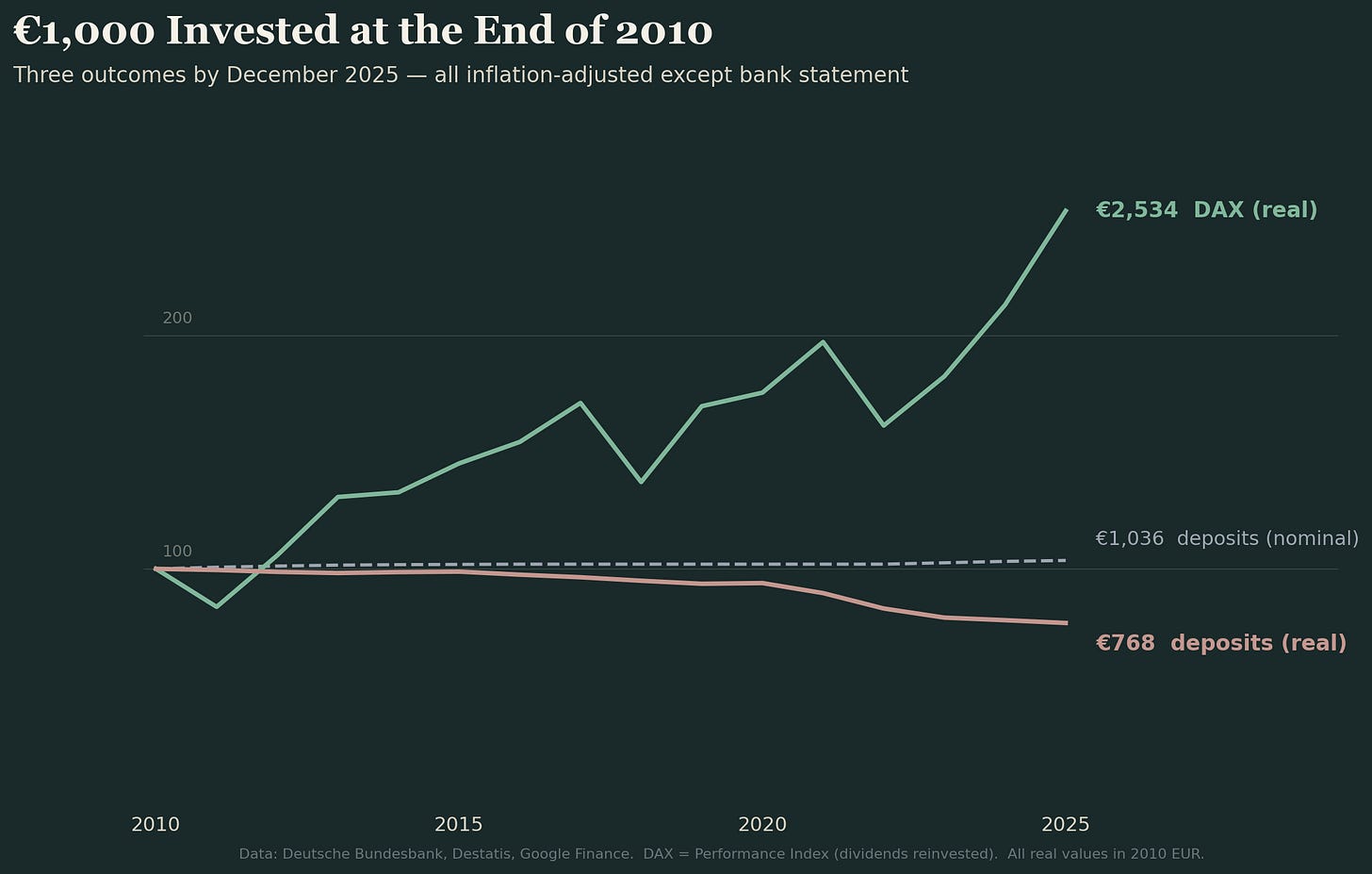

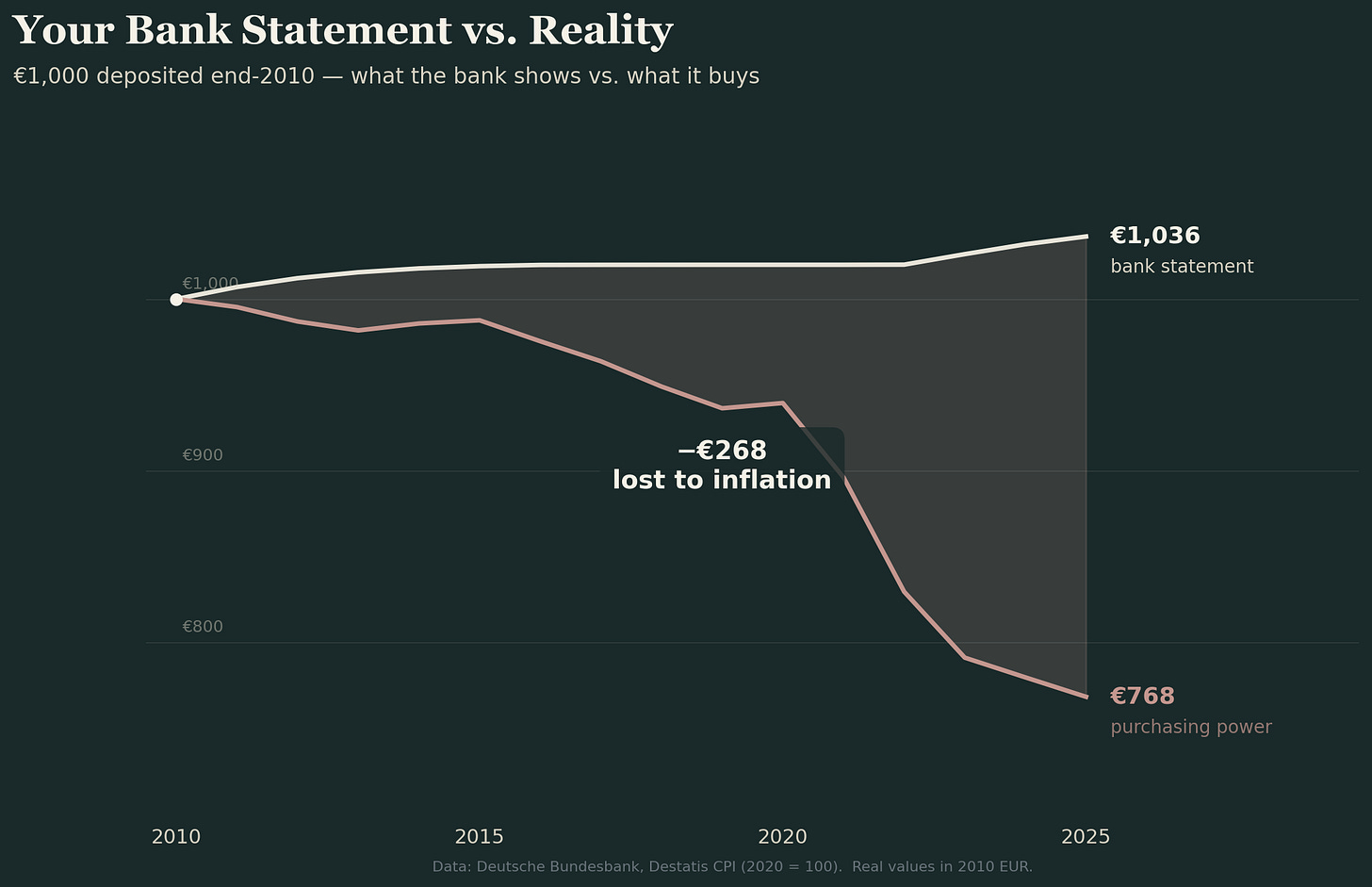

Take €1,000 deposited at a German Sparkasse at the end of 2010. Average deposit rates since then have hovered around 0.3–0.5%. By December 2025, that €1,000 has become roughly €1,036 nominally.

Now adjust for inflation. And compare to a simple alternative — €1,000 in the DAX, the index of Germany’s own blue chips.

€1,000 invested at end of 2010, three paths to 2025:

Sources: Bundesbank MFI interest rate statistics, Destatis CPI, DAX Performance Index. DAX values are total-return, inflation-adjusted.

Your bank statement says €1,036. Your purchasing power says €768. You didn’t really save — you paid 23% for the privilege of safety.

That same €1,000 in the DAX — not crypto, not meme stocks, but Siemens, SAP, Allianz — would be worth €2,534 in real purchasing power today. More than 2.5x your original investment, even after inflation. The “risky” option was German industry. The “safe” option was guaranteed wealth destruction.

Peak pain was October 2022, when real deposit rates hit −7.99%. Your money was evaporating at nearly 8% a year in purchasing power terms.

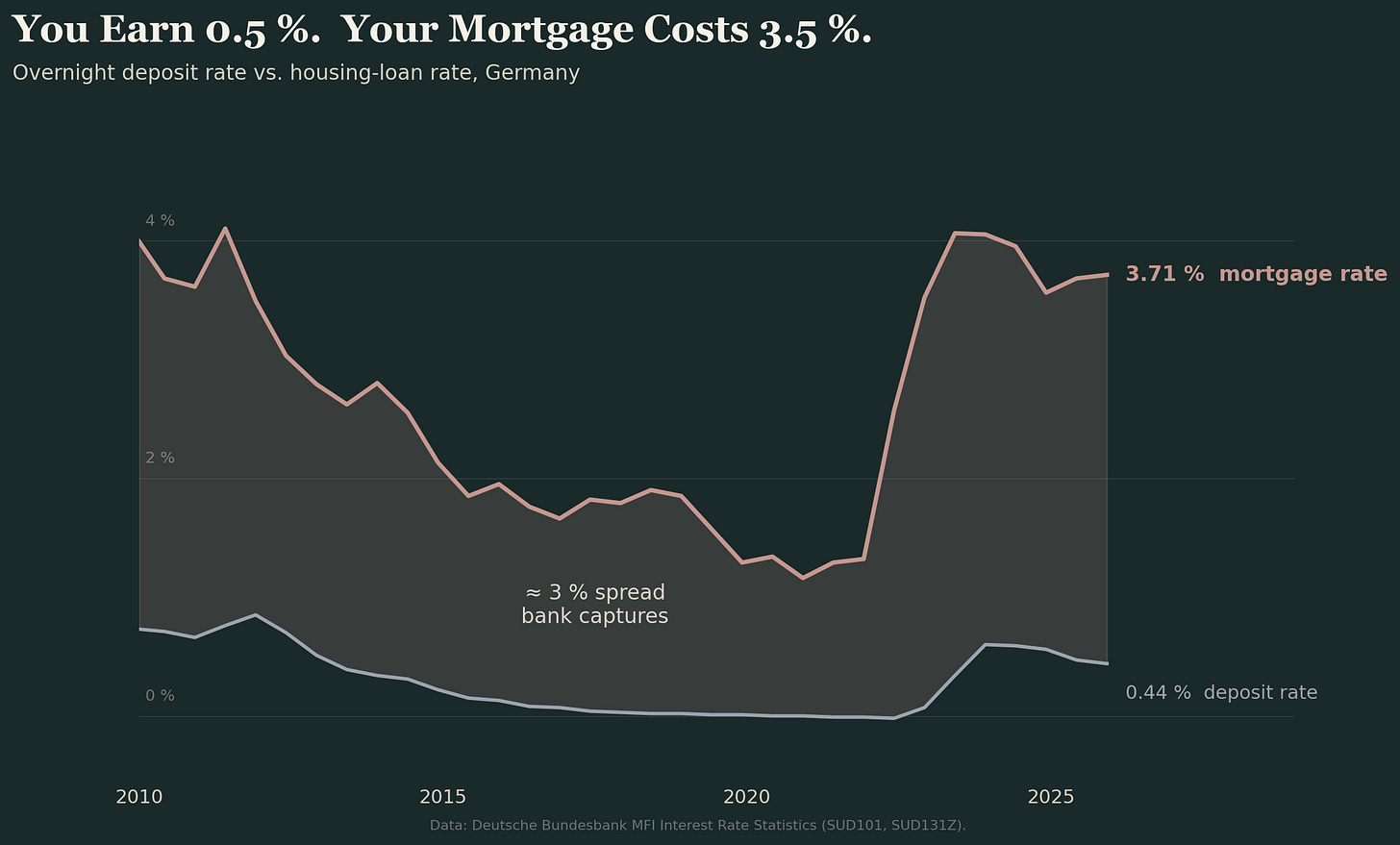

And then there’s the spread. Your Tagesgeld in December 2025 earns 0.44%. Your mortgage costs 3.71%. The bank captures over 3 percentage points for the service of taking your deposit and lending it to someone else. You’re subsidizing the bank, not the other way around.

3. The Twist

Who captured that growth?

Mostly not German households. More than half the DAX is foreign-owned, roughly 53% of share capital. While Germans parked nearly €3 trillion in deposits, foreign investors bought German corporates.

Take just one example — the Norwegian Government Pension Fund, the sovereign wealth fund built on oil revenues, holds €43.5 billion in German equities. That’s 136 companies, including:

Source: Norges Bank Investment Management, fund holdings.

Norway has roughly 2.6 million households. That’s roughly:

€43.5 billion ÷ 2.6 million ≈ €16,700 per Norwegian family

A family in Oslo has a €16,700 claim on German corporate profits. They own roughly €1,440 worth of Siemens alone.

What about Americans? The US system is pretty fragmented — 401(k)s, IRAs, different providers — but the money flows through. Even just looking at Vanguard, their international funds allocate 5–7% to Germany. A typical 401(k) holder with $134,000 and standard international allocation has roughly €1,850 in German equities. Not Oslo-level, but something.

The Norwegian family didn’t choose to own Siemens. Their system chose for them, automatically, through a sovereign fund that invests oil revenues in global equities. The Wisconsin family didn’t choose either — their 401(k) default allocation did it.

The Stuttgart family did exactly what they were told. Save. Be prudent. Trust the Sparkasse. And they watched their balance grow in nominal terms while losing purchasing power, while Siemens tripled, while foreigners accumulated claims on German industry.

Even a clearly problematic system like the American 401(k) — fragmented, voluntary, uneven — delivers something. Germany has close to nothing systemic.

4. The Fork

But it’s gone. The 2010–2025 loss is sunk, that €232 per €1,000 is not coming back. No policy reverses time.

But the next 15 years aren’t written yet.

We’re at €3.0 trillion, right now, and the road splits:

Path A (Repeat): Deposits continue growing nominally, shrinking in real terms. The 2040 generation inherits a larger nominal pile worth less in purchasing power. Foreign ownership of German corporates increases. The same story, extended.

Path B (Redirect): Some fraction of annual deposit inflows shifts toward productive assets. This doesn’t require Germans to become day traders, it requires systemic mechanisms that make equity participation the default rather than the exception.

The mechanisms exist elsewhere:

Auto-enrollment: The UK introduced automatic pension enrollment in 2012. Participation jumped from 55% to 89%. People didn’t suddenly become financially sophisticated, the default changed.

Tax-advantaged equity accounts: Beyond Germany’s current modest Freibetrag limits.

Generationenkapital: The proposed German sovereign wealth fund, €200 billion target by 2036. A start, but it’s state-level, not household-level. And its legislative path remains uncertain after the coalition collapse of late 2024.

The math forward matters. Even a 5–10% annual redirect from deposits into diversified equity exposure compounds into a very different 2040. The mechanism matters more than the specific asset.

A family in Oslo didn’t choose to own Siemens. Their system chose for them. A family in Stuttgart still has a choice, but only if the system offers one. Side note, it’s actually hard to say if this is even a live policy topic right now.

5. The Uncertainty Never Leaves

The above is 1,400 words on the difference between 0.5% and 3% returns.

Meanwhile:

AI systems are already rewriting productivity assumptions

Gene therapies may add decades to healthy lifespans

Fusion pilots are hitting breakeven (well, but you get the idea)

We’re fortunately in a world where some really exciting tech capabilities are growing very quickly. 2015–2020 is incomparable to 2020–2025, and since the end of 2025 a lot of bets are off. Is it even obvious that the deposit-vs-equity debate still matters?

Hard to say. The waters get murky fast.

Transformative tech brings gains nobody forecasted, and problems nobody modeled. Abundant energy doesn’t automatically solve climate. Extended lifespans raise questions about who benefits. The geopolitical map may not hold. Neither might the institutions.

None of that is predictable. But I don’t think it’s much of an argument for parking wealth in instruments designed to shrink rather than grow.

If anything, it’s an argument for having skin in what gets built next, including the European tech story, biotech, and energy infrastructure that will either matter enormously or not at all.

The future is genuinely uncertain. A Sparkasse balance losing 2% real per year is not.

Sources

Deutsche Bundesbank, Banking Statistics. Series BBBK1.M.OU5683 — Deposits of domestic households at banks in Germany. bundesbank.de

Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis), Mikrozensus 2024 — Households by type. destatis.de

OECD, Pensions at a Glance 2023 — Germany country note. oecd.org (PDF)

Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis), Consumer Price Index. GENESIS Table 61111-0002 (2020 = 100). destatis.de

Deutsche Bundesbank, MFI Interest Rate Statistics — SUD101, SUD106, SUD131Z, SUR105. bundesbank.de

Google Finance / Deutsche Börse. DAX Performance Index (^GDAXI). google.com/finance

DIRK, Wem gehört die Deutschland AG? DAX ownership study, 2023. dirk.org (PDF)

Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM), Fund Holdings — Germany. nbim.no

Statistics Norway (SSB), Families and Households. ssb.no

Vanguard, How America Saves 2024. vanguard.com

Vanguard Fund Factsheets (Dec 2025) — VEA, VEU, VGK. investor.vanguard.com

UK Dept for Work and Pensions, Workplace Pension Participation 2009–2024. gov.uk

Bundesfinanzministerium, Monthly Report March 2024 — Generationenkapital. bundesfinanzministerium.de

Methodology: Real values use the Fisher equation with Destatis CPI (2020 = 100). DAX is the Performance Index (total return, dividends reinvested), shown in inflation-adjusted 2010-euro terms. NBIM values converted from USD at 1.08. US exposure estimated from Vanguard fund allocations and average 401(k) balance.

Full processed datasets and raw data available in repository (Link)